A Story for Anyone Who has Ever Loved Halloween . . . or Hated it!

American Halloween

Happy Halloween!

A Halloween Hymn takes the original Dickens story into a form of thematic reverse, but also transports the tale across continents, from winter into autumn, and deep within an different and "darker" holiday. With modern American Halloween as the backdrop, the book unfolds in tone, mood, and content amid a classically imagined New England version of this popular holiday. Explore the development and some signature aspects of the American Halloween that inspired the book.

Pre-Halloween influences

Samhain

The ancient festival of Samhain originated in Celtic paganism to mark the end of harvest and beginning of winter and was observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man from October 31st to November 1st, beginning at sunset. This holiday played importance in various Celtic mythologies and included ideas of otherworldly spirits emerging on that night. Samhain festivals involved gatherings of feasting, alcohol, and contests where bonfires were commonly lit for purposes such as druid sacrifices, divination, and a communal sharing of the fire, where each family lit a torch from the “sacred fire” to return to their homes. One key concept of Samhain was that the boundary between the earthly world and the “Otherworld” was at its most thin and easily crossed.

All Hallows' Eve

All Saints' Day, or All Hallows' Day, is a Christian festival on November 1st to honor of all the saints celebrated by the Roman Catholic Church and several other denominations. Common practices included attending church services and visiting and decorating the graves of the deceased. This observance may have been intended to coincide with or even replace the pagan Samhain. All Hallows' Eve, meaning the evening before All Hallows' Day, developed because many Christians held vigils the night prior to their festivals. This eventually shortened into the title Halloween. Though Puritans were opposed to the holiday, Anglicans and Catholics did bring All Hallows’ Eve with them via their Church calendars to the American colonies. It would be another century before the holiday established any influence but a toehold in America.

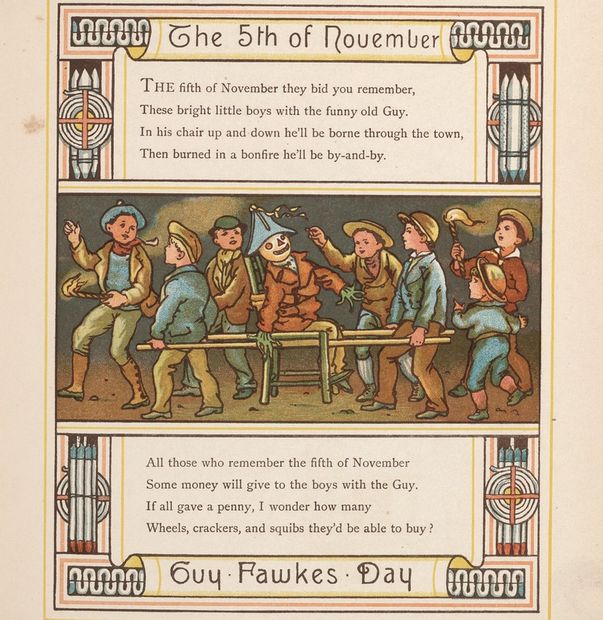

Guy Fawkes' Night

In England, Guy Fawkes’ Day/Night on November 5 arose to commemorate the foiling of the Gunpowder plot by Guy Fawkes to blow up the House of Lords in Parliament and assassinate King James in 1605. These celebrations included fireworks, massive bonfires, burning Guy Fawkes and even the Pope in effigy, and often pranks and rioting. Perhaps being a Protestant replacement to the folk traditions of Samhain or All Hallows’ Eve, Guy Fawkes’ Night also saw some export to the New World. Much of the bonfires and effigy burning were eventually discouraged as being inappropriate or far too disruptive, including by George Washington himself, who forbade the troops under his command to participate.

Autumn Traditions

Bobbing for Apples

Played by filling a tub with water and floating apples which must be caught with one’s teeth, apple bobbing reflects ancient Celtic Roman concepts wherein apples held especial sacred meanings and were often used in divinations and games of the season. Similar games involved catching with one’s teeth an apple on a rod with a burning candle on the other end, or biting apples hung on a string, which in some regions led Halloween to be called "Snap Apple Night.” Discarded apple peelings were used to divine future spouses among many other more spooky conjuring “games.” Such traditions immigrated to the United States in the nineteenth century, most notably with the Irish.

Guising and Souling

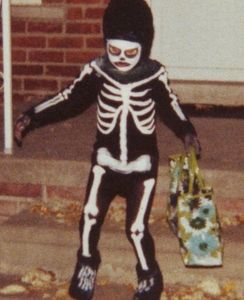

Several traditions led to the modern idea of Halloween costumes. Mumming, where actors perform folk tales in costume, and guising, where children go door to door in disguise for gifts, were part of Samhain from at least the 16th century. Songs were recited in exchange for food and evolved from a tradition of impersonating the spirits of the dead and receiving offerings on their behalf. This idea of role-playing as the spirits eventually led to those in the disguises acting out mischievous pranks as the “spirits” of Halloween. For All Hallows' Eve, children often dressed as the saints they were honoring, and soul cakes traditionally made for that evening were given for those who would then pray for peoples souls in exchange for the cakes or food. On Guy Fawkes’ Day, children took effigies of Guy Fawkes’ from door to door, begging on his behalf, though often the evening activities associated with that particular holiday were far more raucous.

Carving Vegetables and the Jack-O'-Lantern

Another Irish tradition, Jack-O’-Lanterns were made using turnips or other vegetables to be hollowed out with carved faces and carried as lanterns. Said to represent spirits or supernatural beings, they were intended to ward of other evil spirits, and were either carried by children or set on the windowsill of a home for protection. Once transported to America, the practice was adapted for the native pumpkin. Legends of Stingy Jack, also from Irish folklore, told of a blacksmith who in various tales out-tricked the Devil into never taking his soul, which was then doomed to wander the earth when he died as he was not allowed into heaven. The carved vegetables eventually took their name from this character, representing his lost soul caught between heaven and hell.

The Formation of American Halloween

The Irish Influences

Halloween was not much celebrated in America until the 1800’s when the Irish immigrants who flocked to the country brought many of their Halloween traditions with them and it developed into a major holiday by the 20th century.

Halloween pranks

By the 1920’s in many places in the United States, Halloween was getting out of hand with more tricks than treats. Halloween pranksters had become vandalous to the point of being a serious public concern with property damage and even physical assaults among the problems. In an effort to curb young people and guide them into less destructive fun, communities promoted Halloween parties and celebrations, and the idea that eventually formulated into the current practice of trick-or-treating was encouraged.

The Commercialization

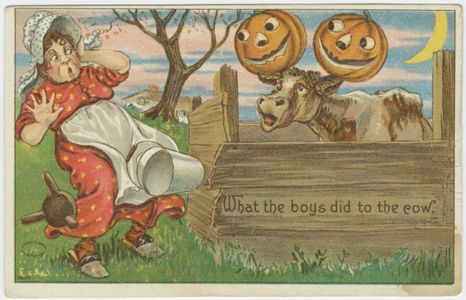

The greeting card industry, along with candimakers, helped formulate Halloween as it would become visualized in the minds of Americans. Greeting cards presented the imagery of cute costumed children, dark but whimsical witches, and comforting harvest pumpkins. The phrase “trick-or-treat” became well known at this time. Specialized holiday candies were produced to coincide and theme with these ideas. By the mid-century, the imagery and traditions were firmly established and began to be further cemented to be Halloween as presented in the films and emerging television programs of the day.

A 20th Century Nostalgia

The “look” associated with American Halloween became a collective sensibility through the designs on many of these greeting cards. Then some of the most lasting imagery came via the Beistle company’s nearly ubiquitous Halloween decorations. These die-cuts of mostly orange and black pervaded the homes and schools of children for decades. Now considered antique and nostalgia, these graphics evoke a mood and atmosphere of a classic “American Halloween” and were a driving visual component in the creation of the text and illustrations of A Halloween Hymn.

Some Classic Beistle Halloween Decorations

Halloween Today.

A Pop Culture Phenomenon

The modern imagery that is now inseparable from American Halloween comes from sources such as Gothic literature and classic horror films. Skull imagery remains a frequent ingredient; a part of the long tradition of mento memori that served to remind of the transitory nature of human life. Christian teachings and art likewise influenced with depictions of devils and the rising dead amid centuries of scenes of the Last Judgment. These themes are reflected in media of film, television, and more every year throughout October.

Black, orange, and sometimes purple have become Halloween's traditional colors.

Munsters Promo Image - History of Halloween

Halloween celebrations

Throughout the United States, towns and cities hold Halloween parades and festivals, while haunted houses and Halloween attractions abound. Some of the most renowned and impressive celebrations are found in the famously "spooky" locales of Salem MA, New Orleans LA, and Washington Irving’s renowned Sleepy Hollow, NY. More commercialized events are promoted in Las Vegas, Hollywood, and Central Florida. It is Anoka, Minnesota, where one of the first Halloween celebrations was ever held, that self-proclaims to be the “Halloween Capital of the World.” No matter where one may be in America on October 31 each year, it is undoubtedly a very “Happy Halloween!”

A Christian Response to Halloween

Superstition and Conscience

Much of the dramatic and thematic conflict of A Halloween Hymn involves Esek Gladstone's repulsion regarding the holiday as rooted in his own charitable sensibilities and accompanying Christian faith. The book is written as an entertaining work of fiction and is not meant to present itself as a final authority on this topic. A thorough and well-reasoned Christian response to Halloween as a secular holiday may be found here.

Copyright © 2024 A Halloween Hymn - All Rights Reserved.